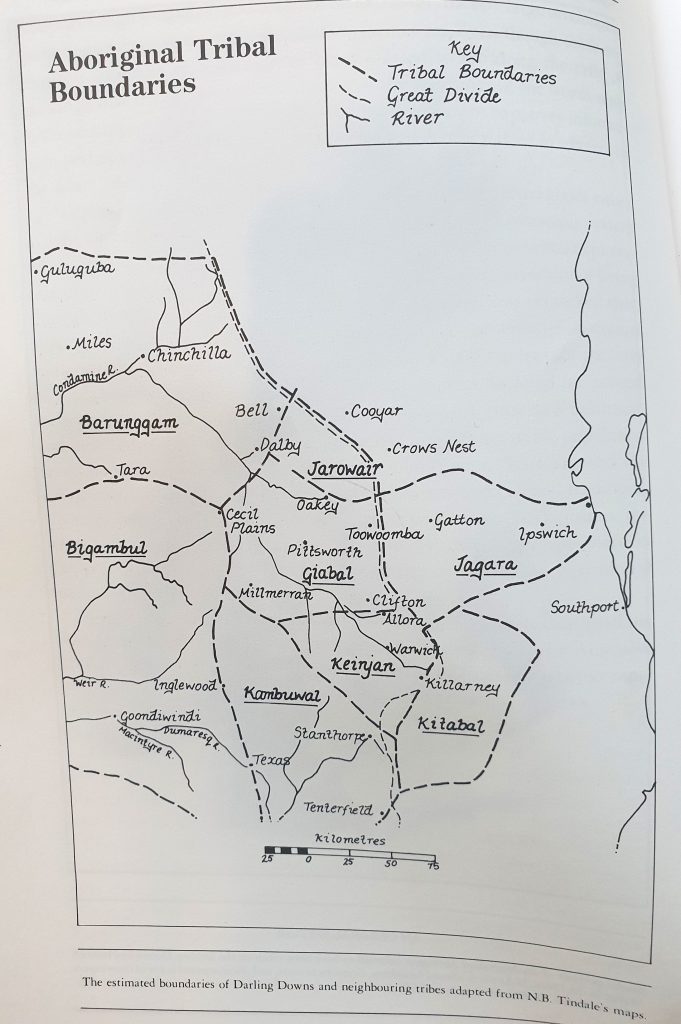

KING BLUCHER’S TERRITORY

When Patrick Leslie came to the Downs for the first time, in 1840, he was not accompanied by any of his brothers. After picking out the country he fancied, which afterwards became Canning Downs and Toolburra Stations, he returned to Sydney with his faithful servant and comrade, Peter Murphy and secured the country. Before returning to the Darling Downs, Patrick Leslie called on the Governor of New South Wales, who was a personal friend of his. The interview being finished Leslie was saying “Good-bye” when his Excellency asked if there was anything he could do for him. “Yes,” said Leslie, “may I ask for the pardon of my faithful friend Peter Murphy.” The Governor at once consented. Peter, therefore, returned a “free” man, and remained with the Leslies until they left the Darling Downs. When Patrick returned with his stock his eldest brother George accompanied him. George had a slight impediment in his speech, and was of a retiring nature; consequently, Patrick took the lead in all business matters.

George chose Canning Downs, and Patrick Toolburra. Walter and William Leslie, the younger brothers, went to India, but a few years afterwards paid a visit to George and Patrick. This was the first time they saw Canning Downs, and as a memento of their visit they brought the celebrated Arab stallion, Tommy, which was a present to their brothers.

When Patrick and George settled down they found that an old aboriginal was King of the Country they had selected or occupied. Moreover he and his tribe were friendly disposed towards the white man, and this friendship became so firmly established that it was never broken. On more than one occasion the Leslies were threatened with extermination by the Macintyre River bloke, but the Canning Downs tribe always warned the Leslies, and possibly out of consideration for their coming to the rescue, Patrick Leslie named the old King “BLUCHER”. “Blucher’s” family consisted of Derby (whose wife was a Macintyre River gin, and a black virago), Toby, Tommy, Nancy and Mary Anne. Derby was always pronounced “DARBY”, and I shall use that form in my notes.

“Blucher” through old age had to resign the Kingship, and the tribe appointed his eldest son, “Darby” as King. I can never forget the object lesson of filial devotion and affection given to we white people by the sons of this old King who, for 3 years before he died, was unable to walk. The sons made a rough ambulance litter of a sheet of bark, in which they placed the Old King’s opossum rug, and carried their father hundreds of miles backwards and forwards over the Range. The old man finally died within sight of the spot where his splendid son Tommy was shot by Inspector Wheeler’s “Black Lambs”. It is not necessary for me to refer further to this unfortunate and regrettable occurrence which ended in Tommy’s death, further than to say it took place quite close to Fassifern Station in the Munbilla district.

THE BORA

As this ceremony formed the bedrock foundations of the laws and rules which kept the tribe together, it can be easily understood that directly the pressure of the white man weakened the functions, and the blackfellow could no longer exercise them, the tribe literally went to pieces. Knowing the aboriginals as I did in the early fifties, and late sixties, no one could hardly imagine that they could have become so degraded in such a short space of time. When I first became acquainted with them in the year 1853 at the Canning Downs Washpool they were very honourable if treated fairly and kindly, and no man ever saw King Darby drunk. I have, however, seen tears running down his cheeks at the sight of his men taking grog.

I shall now tell my readers how I managed to see the Bora ground also give the description of same, which was where this tribe’s final ceremony was held in the year 1858. The site of this was at Killarney, on the south side, where the late Mr Charles McIntosh and Mr J. Dunigan erected their first saw mill. My father and brother were erecting the first traffic bridge over the Condamine river for the late Mr. Fitzallen, at Killarney, between the old farm and the old watermill dam, and I was sent out to look for decking for the bridge. I started on horseback alone for Spring Creek. At that time, there was not a tree fallen above the Killarney township, and the Blue Gums on Spring Creek looked grand. As the late Mr Fitzallen was a man of the same solid principles as most of the old pioneers I thought that he would not put blue gum decking on the bridge, as he really believed in no timber except iron bark. When riding along admiring the timber about 11am it gradually became very dark. I noticed the birds were all flying towards their roosts. As we had no newspapers to give us an idea of coming events, I could not imagine what was happening to the sun, and in a very short time it became quite dark. I had never seen an eclipse before this.

When I was sent out to find timber my orders were to look for Box or Iron-wood, so I rode along the edge looking for Iron-wood, when suddenly I came upon a covered-in avenue leading into the scrub. As the blacks had previously given me a description of the Bora ground, I at once came to the conclusion that this must be the sacred place they called the Bora ground and having heard old hands say that no white man or black gin had ever seen the Bora ground when the ceremonies were to take place, made me very inquisitive to get a good look at the place. However, as I had been told by the old blackfellows that they would kill a white man if he came near the Bora Ground at that particular time I was rather afraid, but remembering a little incident which had occurred a few days previously, this gave me the confidence that they would not kill me, which I now relate :-

The Sunday morning before this I was running in the late Mr George Burgess’ draught horses, a short distance above the old water mill dam which was running strong at the time, and seeing a lot of black piccaninnies (children) clapping their hands, and making a loud noise, I cantered over to see what was the matter. The first thing I saw was a little chubby, fat piccaninny floating down the stream just above the breast of the dam; in a few minutes the little one would have been washed over the dam and dashed to pieces. I immediately jumped off the horse, plunged into the water and caught hold of the child, but the moment I did this the piccaninnies on the bank thought I was going to kill it, and screamed so much that in a few seconds there was a stampede of gins down the hillside like a mob of emus. By the time they got down I had reached the bank, which was very steep and slippery, but being handicapped with the wet clothes and boots I had great difficulty in getting up, so some of the gins took the child from me and held it down or up by the legs, allowing the water to run out of its mouth and nostrils, and in a very short time it was right. Needless to say, the gins were very grateful to me, and in my own youthful way I thought the incident gave me a claim to the tribes sympathy and protection which I afterwards found out really was the case. At all events I hung my horse up and approached the entrance with great caution, expecting a spear at any moment, but I never saw a blackfellow. I always thought the darkness coming so suddenly in the middle of the day had the effect of frightening as the blacks are naturally very superstitious at any time.

The entrance to the Bora Ring was about 7 feet wide and 8 feet high having a large tree at either side with the rough bark taken off and made very smooth. All kinds of animals were printed on the trees in a rough way with raddle, pipe clay and Emu oil. On the right hand tree was a drawing of a ship in full sail, the one on the left having an animal representing the Bunyip or Mochel Mochel, also some huge men with all kinds of animals printed on their bodies indicating some sacred symbols in connection with their laws, similar to the signs of the Zodiac the meaning of which I never could find out. The centre ring was about 30 feet in diameter with poles driven in 5 or 6 feet apart, and about 7 feet high, with their tops all bound round with ti-tree bark about the size of a man’s head. These poles represented the number of young men that were to pass through to each “Kippa” (or youth), and the Councillors knew which Kippa belonged to the different posts. This all signified order and system.

The centre ring was formed the same as a circus ring, only they had an outside ring about 8 feet wide. The Kippas all stood in the outside ring, each youth alongside his own pole. The King and his Councillors stood in the centre ring watching every movement of the young men, and teaching the art of fighting, while a number of men were placed on sentry around the Bora ground, with instructions to kill any man, white or black, who did not belong to their own tribe. The Bora ceremonies only lasted about 3 days. The first day every art in fighting was taught, particularly how to use the Helimon, a shield which was about 2 feet 6 inches long, and one foot wide, with a hand hold at the back. It was made of timber from the stinging tree which is very light, and tough, and would stop any spear, but the war boomerang would split it. The second day was the easiest day, as the Kippas had nothing to do but listen to the councillor’s instructions and advice. The first thing they were taught was to be brave, and the second was to be truthful, as practically all of their messages were carried by word of mouth. This was a most important command which a good black who had passed through the Bora would never break. On this day they were also taught all of the laws belonging to the tribe, and the first time the full significance of the “Mudlo” was explained, which I will describe later on. The third day was the day they were most afraid of, as it was then they had to stand the test against practically every weapon they made use of in all of their fights.

Opposite every post around the outside ring was a clear track cut in the scrub 40 yards long, and every Kippa had to stand at his post straight in line with his 40 yards track, so that it would be impossible to get anything to shelter him from behind. All he had to protect himself with was his Helimon. Each of the best men in the tribe, together with the Councillors, or the Umpires as we would call them, were placed at the end of the 40 yards in the scrub, with practically every weapon they used in war, which were thrown at the young men, and consisted of spears, boomerangs, and nulla nullas. In the event of the Kippas allowing any weapon to draw blood they were condemned as fighting warriors on the decision of the Umpires, as it was possible for a back liner to be hit accidentally. The duties of the condemned Kippa’s were to strip bark to make gunyahs for the aged members, and generally attend to their wants until such time as they did something which was considered brave. Then they would get another chance in their own tribe. This, in my opinion, was the weakest point in this tribe’s laws, as it caused them to be looked upon as cowards, and no woman outside their tribe would marry them, consequently, they usually turned out criminals or sneaked into another tribe and got a second chance of passing through the Bora. Should they, however, succeed they had the privilege of getting back to their own tribe if the King gave his consent, thus getting their tribal mark, but this matter rested entirely in the King’s hands. After the Bora was over the young men were called Kippas, and the King, with his own hands, tied a native dog’s tail around their heads, that was the proudest day in their lives for the simple reason that they could call themselves men, and had the privilege of getting married if a woman chose to ask them, on completion of the tribal mark and tattooing. No man ever proposed marriage. Any aboriginal that was crippled, or suffered from a deformity at birth, was never admitted to the Bora. During the 3 days test the Kippas made an absolute fast, and were under the complete surveillance of the Councillors.

At the conclusion of the tests in the Bora Ring, each warrior teacher brought his Kippa at mid-night, or as near that time as they could guess, to an appointed deep waterhole, which was out of hearing of the females and other members of the tribe. A fire was then made near the water’s edge and each teacher placed a firestick in it so as to be ready to throw it into the water after his boy had been submerged. As soon as the sticks were properly alight the Kippa entered the water and was submerged three times, after this he walked towards the water’s edge, were he stood in absolute silence with the water up to his arm pits.

While here the teacher threw his firestick into the water where the Kippa had been dipped, and if the smoke from it went straight up into the air the King lectured him to continue in the way he had been going and to always respect the King and the tribes laws which would make him a credit to the tribe. Should the smoke curl or twist about on the surface of the water it was looked upon as a bad omen in that, he would be deceitful and not trustworthy, if not always on his guard, and for that reason was cautioned to be always on the alert and to obey the tribe’s laws, otherwise he would die. This part of the Bora ceremony was always kept a close secret from the Kippas, and they never had the faintest idea until they had witnessed it at the water-hole. This superstition held a profound grip on their minds, and had a great influence in their lives, bearing on the laws of the tribe. Possibly, there are still members of the white community who sixty or seventy years ago have seen the aboriginals throwing their fire sticks into the Brisbane River, in front of the steamer they were travelling on. This was to test whether the white people could be trusted or otherwise, in harmony with the tribe’s superstition.

As far as I could learn from the King (Darby) there was an equally strict test carried out by the female Councillors of this tribe, regarding the duties of the females from womanhood. This test was under the supervision of the King’s wife (or gin). More than this I never knew.

TRIBAL MARK AND TATOOING

After passing through the Bora there was still another severe test to complete entrance to the tribe as a full fledged man, viz., to get the tribal mark, as well as being tattooed. After these operations had been completed the native dog’s tail could be discarded. The “Blucher” tribal mark was a hole through the division of the nostrils. This hole was made by using a very sharp pointed bone on the last night of the Bora Ceremonies. This completed, the Kippas had a weeks rest before being tattooed.

Previous to the advent of the white-man the tattooing was done by using the sharp edge of a sea-shell; after that broken glass was used to cut the flesh. The process was for the Kippas to lie on their stomachs on the ground, with a piece of currajung timber in their mouths, which they gripped between their teeth to prevent them from crying out. Should they do this they were at once called cowards – an institution they detested. I believe that they would stand being cut to pieces before giving a whimper. They were a hardy race and their blood must have been pure for the wounds to heal so quickly. After their bodies had been tattooed they filled the wounds with ashes and some kind of oil which caused the wounds to fester and make proud flesh grow over them, giving the appearance of lumps. This completed, they were eligible to be chosen as husbands by their brunette admirers.

LAWS

I now propose to place before my readers a few facts regarding some of the laws of this tribe of aboriginals and would ask the thoughtful, educated, and wide, to think over them and compare them with what they see amongst a civilised, intelligent, educated and Christian community. I have no hesitation in venturing the opinion that they will see much to appreciate in the efforts of a race of aboriginal savages, cut off from all intercourse with the outside world for thousands of years, to keep up the standard of a strong virile race, and the natural laws regarding the internal management working up to that point.

Knowing these men as I did in the very earliest days, before they had become tainted with the objectionable surroundings of a civilised people, knowing the object of the Bora ceremonies, and seeing the symbols on the trees at the Bora Ring, I could not help thinking that at some far back age the original people knew something of the ground work of the Mosaic Laws, and the sign of the Zodiac. The more I think over these and compare them with our present day social life the more I am forced to the conclusion that if ever we hope to become a strong nation, combining all that is good and rejecting all that has a tendency to eat into the vitals of our every day life, we are yet in a position to take a few hints from the teachings of the despised Australian blackfellow.

No 1. The King did not inherit his position by descent, but by proving to the people that he was the best all round man in the tribe embracing strength of character, manliness, truthfulness, reliability, and generally a man to be looked up to with respect. The King’s duty was to see that the laws of the tribe were carried out according to the recognised customs of the tribe. He decided all disputes, and his decision was final. The King always appointed his own Councillors, who were the best men in the tribe. Should he have brothers they were made Councillors. The King had to be a married man.

No. 2. The Councillors were appointed by the King, and in the event of the King’s death, the Councillors chose the next King from among themselves but he had to be a married man. The rank and file of the tribe placed all their grievances before the Councillors, who inquired into them, and settled trivial matters, but important matters were placed before the King, who, with his Councillors, decided what was to be done. Once the King’s decision was given the Councillors attended to the rest.

No 3. As regards the marriage laws, these were quite different from those of white people. The “Blucher” tribe had the three divisions of relationship, which seem to be recognised by all Australian aboriginal tribes. I know they were most particular about their marriage laws when members of the tribe inter-married, which was rare. It was, however, penal for cousins to marry. The woman had the privilege of proposing marriage to the man, but always through a female friend or relative. The man never proposed. If the man refused the offer he at once disappeared. These proposals were always made immediately after the corroborees, where the woman had the opportunity of seeing the men from other tribes, and picking out their choices. As a matter of fact, it was “Leap Year” all the time for the belles of this tribe. If the man was agreeable a time and trysting place was arranged, through the third party of course, which sometimes took a considerable time to fix up. Suddenly the gin disappeared, and for 3 weeks with her husband, kept to the bush on their honeymoon, when the husband took his wife to his own tribe. If any number of the tribe objected to the marriage he had the privilege of fighting the newly married man, and the same remark applied to the wife’s relatives but in their case they had to go to the husbands tribe and fight there. Under these conditions, the visitors received a safe permit provided there was no old grievance. After the fight the visitor returned, but never brought the woman back if he won.

I have known cases of jealousy in these marriages, but I should say not to the same extent as with white people. Jealousy was unknown before marriage, as there was no courtship. Widows and elderly gins who had not the same opportunities of marriage could marry the men who failed to pass the Bora tests, but this was not at all a common practise.

No. 4. If a man or woman committed adultery, or murder, within their own tribe they were immediately condemned to death, and had to escape to another tribe or suffer the extreme penalty. If, however, a man or woman murdered the member of an adjoining tribe their own tribe protected them. This left it to the adjoining tribe to retaliate and kill the murderer, if possible, failing this, then any other member of the same tribe, at the first opportunity. This, in the writers opinion, was a weak spot, as it always led up to tribal fights, and in comparison with our present day brought about very much the same position as that of Serbia and Austria.

No 5. Breaking any of the moral laws except murder and adultery, was excused twice, with a caution, and on the third occasion the extreme penalty would be carried out at the first opportunity and without warning. Knowing this, the culprits always, when possible, escaped to another tribe and took his or her chance with them always remembering that the tribal mark laid them under suspicion. It was to a great extent that the Native Police were recruited from such men, and the latter took every opportunity, under the protection of the uniform, to carry out their villainy with other tribes. When this became unbearable to their officers they invariably absconded and then encouraged the other aboriginals with whom they mixed to carry out murders of the whites or outrages on the white woman.

No. 6. As no execution could be carried out without the consent of the King, it was usual after this had been given, for his Councillors to find a suitable spot for execution. This was generally chosen on the edge of a scrub or a thickly timbered ridge. The victim was always included in a hunting party forming the last group, which was composed entirely of Councillors, and when his position was close to a large hollow tree which had previously been selected, he was killed by the man following him using his tomahawk and opening the skull. No one but the Councillors witnessed the execution. As climbing vine was always used to put around the victim’s neck, by which he was drawn up and dropped into the hollow tree. Not a word was spoken by the executioners during the proceedings. The hunt went on as if no execution had taken place, and was, in my opinion, a very humane way of despatching criminals.

No. 7. The burial of the dead was strictly carried out of hard and fast lines. Only the law-abiding members of the tribe were, at death buried in the ground with full tribal ceremonies. Criminals and law breakers were always placed in hollow trees. As regards the law-abiding members, the manner in which the bark and sap of the trees adjoining and leading to the grave were tattooed by tomahawks, indicated whether the grave was that of a male or female, also if the former was a King, as follows :- for a King each tree was marked on the inside facing each other, that is right and left along the track the corpse was carried, as well as that every alternate tree bore a distinctive mark allotted to Kings only, which was always placed above the tattoo marks. For a Councillor the same marks were given except that his distinctive mark was placed by itself on the opposite side of the tree. Men were always buried between two large trees. For a woman the trees along the track were tattooed only on the left hand side of the tree, with a distinctive mark only for the Queen, above the ordinary tattoo marks. These distinctive marks always impressed upon me the supposition that they had as their origin some reference to a religious symbol such as the “Trinity”. In passing, I may add that this information was given to me by a councillor who showed me the tattoos on a tree heading up to the grave of a member of his tribe and who, in life, I knew personally. To be thoroughly understood the trees should be seen. After the body was buried a post or stake was placed at the head of the grave, which signified that no member of the tribe was to hunt or kill game within sight of the grave for 12 moons. It always struck me as having a distant connection with the origin of the present practice of Chinese in placing food on the graves of their dead.

No. 8. No boys or girls were allowed to associate together; after the boys were 6 or 7 years of age they had to camp with the young fellows who had not been through the Bora ceremony.

No. 9. The girls remained in their parents camp until they were from 7 to 8 years of age. After that they had to camp with the old women and widows.

No.10. It was the duty of the old women and widows to teach the girls to cook the food and train the children, also to make dilly Bags of all kinds (used to carry their food, etc) kangaroo and wallaby nets, and particularly opposum skin rugs, as every member of the tribe had one of these.

No.11. From the time the boys went into camp by themselves they were regularly trained by the men who had gone through the Bora in the arts of hunting, tracking, the use of all implements of war, and the methods of attack and defence.

No.12. When camped near water the sexes were not allowed to bathe together. The males were allowed to bathe in the forenoons and the females in the afternoons. Any breach of this rule meant death to the offender. Every aboriginal from childhood was taught to swim. Further than this each child was taught the art of rescuing a drowning person, and my experience taught me that it was almost impossible to drown a blackfellow owing to the way he could use his feet, making it possible for the weak person to get way from a stronger one.

No.13. The law regarding fighting among themselves was that if two men had an argument which could not be settled the King at once ordered them to fight it out, during which no person was allowed to interfere until one saw he had enough; then the best man had to cease at once. Should, however, he persist he was at once knocked down with a nulla nulla. If a young man and an old man had a quarrel the old man could use a knife, but not the young man until he could produce a grey hair on his head. If neither men would fight then they had broken the King’s instructions the King walking away, whereupon the Councillors immediately took control, which practically meant that the brawlers had been silenced, and knew what the result would be if they persisted, such as indicated in No.6. As a rule Kings only fought Kings of other tribes and never fought with, or drew blood from, any member of his own tribe.

No.14. No young man was allowed in a married man’s camp, but if a married man wanted to interview a single man on any subject he could go into the single man’s camp and converse as long as he chose.

No.15. The men who failed to pass the Bora tests had to strip bark for the gunyahs of the old men, women and widows, also for themselves. These men held no standing in the councils of the tribe.

CORROBOREE

After the tattoo marks on the Kippas had quite healed the tribe began to prepare for a large corroboree, which usually followed one of these functions. The Kippas were not allowed to hunt side by side with the best men in the tribe. The King picked out a certain number of men and sent them out in different directions, some to get plain turkeys, others scrub turkeys and Wonga Pigeons, others fish and any kind of game that came in their way. They had instructions to bring in as much as they could – enough to carry the whole tribe and any visitors through for two or three days, on the basis of share and share alike. This was pure socialism. This part of the programme being ready the corroboree began after dark, and took the form of a kind of dance by the men, commencing about 7pm and continuing until midnight. These men had all passed the Bora.

The women sat on the ground with their opposum rugs drawn tightly over their legs, with a broken boomerang, beat tune on same, and sang to an accompaniment resembling the music of muffled drums. The men were all painted alike with pipe clay, and would put one in mind of a regiment of Highlanders dressed in tartan, particularly the legs. Their hair was put up in a large knot on top of their heads, with three frills of different coloured feathers, surmounted by a dozen white cockatoo feathers. These represented their crown of honour, an emblem of purity, and they would sooner die than dishonour it. You could not insult them more than by selling these feathers; they would kill you on the spot.

The old gins always had the place of honour in the front row at the men’s backs as they were dancing, and the younger people in the background, all beating time on the opposum rugs, or clicking two broken boomerangs together, which was a sight worth seeing, particularly when several hundred men took part. These men were as straight as trained soldiers, all active athletes, as full of bravado as the best white man, at time appearing intoxicated with excitement. To the white observer, the corroboree seemed to be always the same, that is, the movements of the men; but as a matter of fact there were as many variations in the different corroborees as there are with the white people when playing different pieces of music. The corroborees were representations of the aboriginal methods of killing their enemies, as well as every form of hunting and capture of game. In other words, they gave the same enjoyment to the aboriginals as our best operas do to us.

The new corroborees were eagerly sought after by the different friendly tribes, and carried out as I shall indicate further on. The composers held the same position as ours do in the public estimation.

GOOD-BYE

The next morning the scene is changed as the visiting tribes prepare to take their departure for their own happy hunting grounds. This is the time the gins show their affection for each other, standing in groups of from 5 to 8, with their arms around one another, resting their heads on the shoulders and breasts of those they love the best, sobbing and crying in a most piteous way. This reminded me of a scene witnessed in the United Kingdom over 60 years ago at the departure of an emigrant ship for the Colonies.

Before starting in the morning there was a general consultation among the heads of families as to what distance they would travel and where they would camp for the night. This was a matter the gins had to decide, and it took some time to settle the business. The men on all occasions left this to the coloured ladies, and it often caused a good deal of difference in opinions and sometimes ended in unpleasantness, as the younger people had less to carry than those with young children, so the latter usually fixed their distance to suit the old women and men who could not walk as well as the younger members.

While the young men were travelling it was their duty to secure as much food as possible for the night. The lads usually got what old bushmen called “sugar-bag” or “cubi” the aboriginal name for a beautiful clear honey made by the Australian stingless bee, which the piccaninnies were very fond of. As the shade of night came on, they all drew into camp and fires were lit to prepare the evening meal.

METHOD OF LIGHTING A FIRE

Lighting a fire on a cold wet night in the bush is sometimes a great difficulty to practical white bushmen with matches, but on this point, as on many others, the blackfellow excels the white man, as nature provides him with matches without his own making. They get the old grass tree top that is decayed, dry inside, and hollow, and into this is placed some dry stringy bark rubbed fine. Then the long hard round dry stem belonging to the same tree is placed inside this hollow, and by the quick action similar to sponging a fowling piece, friction is caused which makes fire in a few minutes. I have known bushmen in the early days in the “Blucher” country, to get great relief, indeed saved from suffering, by this form of fire making.

METHOD OF COOKING FOOD

The blacks roasted all of their food on the coals and in the ashes, with the exception of fish. For this, they dug a round hole in the ground with a yam stick, about 18 inches in depth, into which they put rough stones and made a large fire over the top of the hole. The hot ashes and coals falling down through the stones made them red hot. The heat from the stones cooked the fish in a very short time after they were laid on top of the stones. They had no utensils of any kind for cooking food, and they never drank any water until they had eaten their food. As a rule they were very fond of fresh meat and mutton, but had a great prejudice against salt meat as they were accustomed to eating everything fresh, and had no taste for salt. The food the gins prepared for the young children consisted of scrub yams, which, when dug out of the ground, were very much like sweet potatoes but much drier when roasted in the ashes.

NATIVE BREAD

The only food this tribe had to represent bread was made from the cunjevoy – a very poisonous plant when not cooked, as many a white bushman knows to his sorrow; I knew one white man who died from tasting it. The blacks were very fond of this root, but few would take the trouble to prepare it properly because it took a long time and a great deal of patience to do this. In appearance it is very like arrowroot, but looked so nice and juicy with a large bulb very like a white turnip that it would tempt a person to taste, but if done, the result was disastrous. The tongue swells instantly, and the eyes stand out of the head as if one was going mad, while the pain is intense. It grows in the mountain scrubs. In conversation with my old and respected friend the late Dr A.O.H Phillips, I asked him if he had every seen this plant, and he said “No,” but he had a case of a man from the bush suffering from the effects of tasting it, and he told me the man died in the Hospital, the inflammation having gone down the windpipe on to the lungs. The blackfellows method for preparing it was to peel off the outer skin and then pound it down with a flat stone on a clean rock at the edge of a running stream, where it could be well washed which helped to take the poison out, while cooking in the ashes removed the last traces of poison. As it took from 3 to 4 hours to prepare this food, the young people would not go to the trouble, so it usually fell to the old people to do this work. The paste would then be worked up into small dampers about 6 inches in circumference and by an inch and a quarter in thickness. These they would put into the hot ashes, covering them up in the same way as we would a damper, so as to prevent the air getting into burn them. When taken out of the fire one could scarcely tell the difference in appearance from the real damper. I have tasted them, but cannot recommend the food, same tasting very much like bread made from bran and pollard. The aboriginals were very fond of it soaked in water and gave it to their children.

WAR AND HUNTING IMPLEMENTS

No.1. The Fighting Boomering:- It will be noticed that I have always used the word “Boomering,” not “Boomerang,” because the latter word was a whiteman’s “Cockneyism.”

The fighting boomering is a larger, flatter, and heavier weapon than the others of the same name, slightly bevelled on the one side and was always used where great force was required, when thrown it skims along at an even angle above the ground about the height of a man’s chest. I never saw a “Helimon” used against this vicious weapon, the blackfellow’s mode of escape was to throw himself flat on the ground. This weapon was always used in war, also for killing kangaroos, emus and dingoes.

No.2. The game Boomering: These were generally used for killing all kinds of flying game.

No.3. The sporting Boomering: This was much lighter than either of the above and required great skill in making. In a bough was the fire and steam principal of bending to bring it to the proper angle employed. When completed it was slightly longer at one end, and in shape was more of a half circle than the other two. The weapon could be thrown so as to complete a circle and come back to the thrower’s feet. These weapons were used to train the Kippa candidates and younger boys in the art of throwing and making boomerings.

SPEARS

No.1. Spear:- This was a large barbed weapon usually from eight to nine feet long with three barbs, two on one side and one on the other. This was used in tribal fights and for spearing large fish, and was made from myall timber.

No.2. Spear:- This was similar to No.1. only not barbed. One end was finer than the other, and was specially meant for spearing large kangaroos; the big end was used for rougher and heavier work. I have known a man to go into the bush with this spear and within two hours return with the skin of the largest kangaroo, and as much of the carcass as he required.

No.3. Spear:- This was a lighter made spear and was barbed. It was used for spearing fish. It was usually from seven to eight feet long, and was also used for spearing small game. Any spears that were barbed were only barbed at one end so as to make it possible to easily take them out of anything speared.

NULLA NULLA

No.1. Nulla Nulla :- A very heavy weapon similar to the old war clubs used by our own ancestors. It was made from the toughest and heaviest timbers, weight being essential. After the advent of the white man, hobnails were driven into the head of this nulla nulla in rows as close as possible for a distance of three inches from the top. This was indeed a ferocious weapon always being used at short arm work and never thrown.

No.2. A similar weapon but lighter; it was principally used in the kangaroo hunts. It was used for close work, or could be thrown. In the hands of a strong man it was a deadly weapon.

No.3. A much lighter weapon than either of the preceding. This was always thrown at wallabies and was much lighter and finer in the handle. When in the hands of an expert it was usually thrown so that the smaller end struck the animal and passed through the body.

MUGGIN OR STONE TOMAHAWK

This was made from the blue metal or whinstone to be found in our basalt country about the mountain precipices. This was the hardest of all implements to make, as it required a lot of grinding in rough sandstone rock at the edge of the water. It was also difficult to cut the grove about the centre of the weapon to hold the vine?, which was usually put on so as to tie on the handle similar to that of a blacksmith’s cold iron cutter. The material used to complete the tying on of the handle was leather-wood bark cemented with the gum of the pine tree and opposum hair. When this was completed it took a very sharp and strong implement to cut it. After the handle was secured the grinding process of the blade began. This took a very long time to complete. When finished it would not at the very best cut timber, and was not at all a desirable implement or tool with which to square timber. There were two kinds of tomahawks, one for stripping bark, with a longer handle than the other and much lighter.

EAGLE’S CLAW

Prior to the advent of the white man’s knives, this tribe used the dried claw of the eagle hawk for a close infighting weapon. When securely tied to a short handle just sufficient to get a hold; it tore the body in a frightful way. Our present day shoemaker’s knife displace the eagle’s claw.

HELIMON OR SHIELD

This weapon was used for precisely the same purpose of that of our ancient European warriors. It was made out of stinging tree wood, which was very light and soft, but tough, and was about 2 and a half feet long, and from 10 to 12 inches wide, according to the strength of the man using it. In appearance it was very like the shell of the fresh water turtle without the head and legs only much larger and thicker. On the centre of the inside flat surface a hand hold was cut out next to the body of course. Armed with one of these the aboriginal warrior could defend himself against any of their weapons except the fighting Boomering, which on all occasions would split the Helimon after the second blow, but the spear, nulla nulla, and stone tomahawks could be easily warded off. Once the Helimon was disabled the aboriginal warrior had to rely upon the trees for shelter, or whatever else he could obtain.

BATTLE AXE

There was another dangerous weapon, the name of which I now forget. In appearance it was very like the common mortising axe, and was made entirely of wood. The handle was anything up to 1 ½ inches thick, the blade being about 2 ½ inches wide, sharpened at the point and both sides like the edge of a boomering. It used to make me think of the pictures of the old battle axe, only it was lighter and longer.

OTHER IMPLEMENTS

The Climbing Vine:- The vine used for climbing trees quickly was about three quarters of an inch thick, and usually about nine feet long, unless required for very thick trees, when it was longer. In appearance, it was similar to a grape vine at the base, throwing out limbs of all sizes and lengths, which could be used for all purposes. Before a vine was used it was thoroughly tested against a strong young tree, by looping it around like a rope, two men grasping either end and pulling the tree with all their strength. If the vine stood the test it was considered safe for any use at any height. The thinner vine was used for climbing after game or “sugar-bags” (wild honey). When using the vine the aboriginal, male or female, made a knot at one end which they held, and placing the vine around the tree, immediately began climbing by pressing their feet against the tree, raising the vine from different positions as they ascended. When high enough up they cut a nick or notch in the tree and after giving the vine a turn once around the calf of their leg, secured the right hand end in this nick between the toes by pressing the foot into the nick, thus freeing the right hand to use the tomahawk.

They were expert at stripping bark for gunyahs, and showed great science in performing that work, bringing down as many as six sheets from the one tree, by expert use of the vine, without injuring a single sheet.

As very few people know what this means I shall try to describe it, although it should be seen to be properly understood. The native knows that the top bark of the tree is thinner than that at the bottom, and begins operations at the top by going up sometimes forty feet. After the sheets have been cut top and bottom, and once up the centre in lengths of about six feet they are gradually loosened from the sap of the tree by the handle of the tomahawk. The aboriginal then shifts round to the back of the cut, and prizing up the bottom end from resting on that of the tree, gets the sides on to his vine, and in a series of jerky movements descends with his load to the ground. In comparison the white-man could only strip two sheets and cannot compare with the aboriginal.

NATIVE BUCKET OR COOLAMAN

Before the white man came on the scene with his tinware the aboriginal had to invent something to carry water when travelling in waterless country between certain camps. For this purpose he used the joints of the palm tree which grows on top of the main range. This tree was cut in lengths about the size of a paint or putty tin, the bottom being the original joint division of the tree which runs right through from side to side. Larger buckets could be made according to fancy. To carry these coolamans a hole was burned and worked into each side by anything hard and a tough vine made into a handle. Besides carrying the water for drinking it was always necessary to have it in case of snake bit when it was used for rinsing out the mouth as described elsewhere.

HUNTING GAME AND DISTRIBUTION OF SAME

Kangaroo Drive:- The day a kangaroo hunt was to take place was looked forward to as a day of great sport and pleasure, owing to the men and gins being allowed to take part in it. The joy and excitement to the blacks was on a par with that of the picnic races to the white people at the present time in the same district, because each gin, young or old, had the privilege of backing their favourite man to kill the most kangaroos. The evening before the hunt took place two or three cautious men were sent out to discover where the largest number of kangaroos were and also the best position to set their nets. These were usually placed in a narrow and deep gully where there was a waterhole. Next morning the strongest and ablest men were despatched with the nets, which were about 30 yards long and 4 feet high. These were tied to saplings or young trees in a half circle around the waterhole about 50 yards back, with strips of the inside bark of the Currajong tree. Generally, 8 nets were used. On completion of this work one of the men went to the top of the nearest hill and set fire to a dry grass tree. The under part of the grass tree is always dry and the upper part green, consequently, when set on fire volumes of very dark smoke are sent up, which are easily seen by a signal man who is standing on the nearest hill to the camp. This is the signal for all hands to form the circle around the kangaroos, starting at the camp, and extending right and left for miles around until the men guarding each end of the nets are met, thus forming a complete circle. All being now ready the signal man lights another grass tree which was bound to be seen by someone in the circle; signs were then passed long the line from one to the other, as no one was allowed to speak or make the least noise, but close in gradually around the kangaroos. Up to this stage one would not have known there was a person in the place. Afterwards, however, the yells and screams of the men and women, made a perfect babel of noise. As soon as the kangaroos see the first man, they make in the opposite direction, only to meet another man. They begin to bound about in all directions, meeting men everywhere, thus, becoming more frightened and stupefied.

The drivers were then silently but swiftly closing in on the kangaroos, and when in sight of the nets, the principal driver gave a terrific wild yell, which was followed by the three sides of drivers, but the men near the ends remained as quiet as mice. The kangaroos try the nets and finding themselves surrounded, the “old man” kangaroos turn on the blackfellow and show fight. Then the real slaughter takes place. The gins, young and old, who have been closely following their champions now come running in, laughing, screaming and clapping their hands, completely intoxicated with excitement, but keeping back a fair distance so as to be out of danger. What with the men clubbing the kangaroos the yells and screams of the men and gins, added to the hissing of the kangaroos not disabled, finding it impossible to escape, I may add, jumped into the waterhole on top of each other, whereupon the men jumped in after them, some using waddies, others tomahawks until the last kangaroo had been killed. This is one of the most amusing scenes in the blackfellow’s programme of life. The kangaroos are sometimes fierce “old men” measuring from 5 to 6 feet in height, and very powerful. On many occasions the hunters got badly torn about with the kangaroos hind claws. The slaughter being over they pulled down their nets, rolled them up, and each on taking as much kangaroo as could be carried, started off to camp in the best of spirits. That night a great feast would take place and all the daring deeds rehearsed and talked over until near midnight. The following day there was nothing but eat, and sleep.

WALLABY HUNT

The aboriginals of the Darling Downs were true Socialists as far as food was concerned. It was both amusing and interesting to see them at a kangaroo or wallaby hunt, when there would be from 200 to 300 men from the oldest warrior to the youngest boys, who were as naked as the day they were born, formed a circle around a point of scrub about 2 miles wide, opposite another point of scrub, where there was a stretch of forest between. When the circle men began to close in on the wallabies the latter would make a break for the opposite scrub across the open forest country. Then the fun would begin as the wallabies had to encounter a line of the smartest young men in the tribe, stationed about 200 yards from the scrub, with a sufficient distance between each man to be out of the danger zone as regards nulla-nullas. Next came a second line, the latter always divided with the drivers. It is most amusing, behind that still another line of old men, boys and dogs. All the men outside the scrub kept as quiet as possible, but those inside it made the most hideous noises. Hearing all this noise the wallabies became stupefied and were easily killed by their pursuers. This was a sport they delighted in, the faces of the old and young beaming with excitement.

DISTRIBUTING THE GAME

Now came the distribution of the spoil. The young men in the first line always had the lion’s share, as they had the first chance. Some of the most active men would often kill from 6 to 10 each. As the drivers were mostly young men, and being in the scrub had not the same opportunity as those that were in the first line, the latter always divided with the drivers. It is most amusing how justice adjusts itself even amongst savages. After they all had a rest and a smoke (even in my day every man, woman and child did this) they began to pick out the fat ones exactly on the same lines as a butcher would examine fat sheep. The first line men always had the pick of the fat wallabies if there were two coming at the same time, leaving the poor one to be killed by the second or third line men. The first line men and drivers having picked out all they required, provided the camp was not too far away, all of the aged women and widows had the first pick of what was left and no one dared touch the game until these were satisfied. The gin always knew when the drive was over by the noise ceasing. In the event of the gins not being able to come along the King picked out the best that were left and made the boys and men carry them along to the camp for the old gins, and what was left then belonged to the old men.

EMU BATTLE

When a flock of these had been located the blackfellows used a good deal of strategy and cunning to effect this purpose, which is the death of as many emus as possible. They are very fond of the flesh of this large bird, and have a weakness for the oil. Another choice morsel is the heart which is usually large in the emu. The hunters of the tribe first of all approach the edge of the plains with great stealth, because as a rule the emu is to be found grazing where the grass and herbage is sweet. Watching closely they soon find out which part of the timber the birds are likely to make for, and disguise themselves by hanging and tying bushes about their bodies so as to look like the surroundings whereupon they wait for the unsuspecting emu in the usual half circle formation. Here again, as in the wallaby drives the men are spaced sufficiently wide apart to be clear of the danger of the nulla nullas. Once the warriors are set the best mimic of the tribe is placed in centre position. This man is an adept at the call of the young and adult birds when is distress, and used his powers as a decoy. Directly the unsuspecting birds are within hearing of the calls they very soon come to see what is the matter, and when close enough to the pivot man the latter makes a raid at the nearest bird with a wild whoop, which is the signal for the wings to close and circle the emus. First of all nulla nullas are used, after this should any of the emus get through the cordon, the war boomerings are brought into use. These are deadly weapons in the hands of such men as composed the Blucher warriors. The only escape from these is to lie flat on the ground. The war boomering was the only weapon which was not thrown with full force at the “Bora” tests. Moreover, the gins did not participate in the emu hunts. At the conclusion of the hunt the warriors always took what they could carry to the camp, and should there be anything left it was placed in the forks of trees, and the camp men who failed to pass the Bora test were sent to bring it in for the aged members and themselves.

THE PLAIN TURKEY OR BUSTARD

These birds have a pecularity in that they always start to walk away from any disturbing influence, and the usual procedure is gone through by placing the hunters in a half circle in a crouching attitude, disguised by bushes. The drivers have to be particularly careful not to get too close and have to exercise great cunning to see that none of the birds have young ones with them, should, however, this be the case which is always recognised by the mother being inclined to squat and hide, they must be avoided only keeping the male birds walking towards the centre hunter. Directly the danger zone for the turkey is reached, the centre man gives the signal, but up to that he has been making the most pitiful calls of the young bird. The wings then close in and the birds immediately start to fly. The war boomerings are used against the birds on the wing and the execution takes place in a terrible way. Of course, these boomerings can only be used with the birds flying, and are never brought into play while the turkeys are walking owing to the danger they would be to the men themselves.

THE SCRUB TURKEY

As the heading will show, these birds live in scrubs and brush and there were several ways of capturing or killing the. In the ordinary hunt through scrubs or jungles in day time the warrior kills the birds by sneaking and main use of the nulla-nulla when the birds have flown up into the trees. Again they mimic the cry of the birds, who, when close enough are startled and made to fly up on the limbs. When there is to be a feast, or something out of the common, another method is used to get a supply of scrub turkey, the time being a clear moonlight night, when a raid is made on the roosts about 10 pm the roosts having been previously located during the daylight rambles. The signs of a permanent roost are the droppings to be seen on the ground below. These roosts are visited by a certain number of men who give the call and the birds startled, immediately put their heads up and are cut down by the boomerings. It must be clearly understood that these night trips are rare because an aboriginal has a peculiar dread of being out at night, particularly in a thick scrub. There is still another method used by the gins and their children in the time of drought when water is scarce in the scrubs. The children cut boughs and bushes with which the gins fence in the water soakages, similar to a small bough yard having holes for the turkeys to walk through. At each of those holes a slip noose is placed, made of leather wood bark, a material as strong as the best hemp. After these traps are set the gins and children go away and root out yams same distance off, looking at the nooses on their way home in the evening. Should there be no captures the traps are visited early next morning, which is particularly the case when the aboriginals are camped near the scrub. At certain times of the year a close watch is kept to find out the new nests which are made entirely by the male birds. These nests are huge mounds of scrub leaves, mould and thin dead sticks. The fine mould is placed on the bottom by being thrown backwards by the birds, on to the sticks; it then falls through as from a sieve. It is in this fine mould that the hen lays her eggs and up, in a circle around the mould. Then comes the leaves and coarse soil on top of the eggs. After this the main top consists of fairly large rotten timber and large leaves etc. The eggs are hatched by the internal hear of the mound, which is aggravated by the showers of rain and sun’s rays. When the young birds are hatched they find sufficient grubs and insects in the mould to keep them alive as they work their way out from a depth of 2 or 3 feet. On reaching the top layer the old birds call, and out jump the chicks which are from that time capable of running or flying away from danger. The young birds are a great luxury and the fresh eggs are just as nice as our ordinary turkey eggs.

THE WILD DUCK

In capturing these a great deal of intelligence and cunning was required, and I received a proper object lesson in witnessing the process for the first time. Except in flood time the waterholes and creeks always had large beds of weeds which grew out towards the centre of the holes, the roots being under the water. As a rule the centre of the holes were the only place clear of weeds, and if ducks were found in the holes they invariably swam out to the centre before flying. The blackfellow always chose the holes where he could either stand up or where it was shallow enough to lie down under the water, and, at the same time, under the reeds. Having located the ducks on a waterhole of this kind, with a bend in the banks, the trappers at the far end of the hole got themselves ready unseen by the ducks and took up their position across the hole in alternate rows from side to side. Before going under the water each man plugged his nostrils with wood, but in my time rag was used. They also placed a hollow reed usually 6 or 8 inches long in their mouths, after the style of the present day submarine periscope, the top of the reed being out of the water, through which they breathed. As the top of the reed appeared to be part of the weeds the ducks did not notice it. The trappers either stood up or laid prone, eyes open, looking towards the surface. In the event of anything going wrong with the reed the trapper pulled a handful or two of weeds, placing them over his face and nose, and raising them above the water level breathing serenely through the reeds. Everything had to be arranged with a mathematical certainty, particularly as to when the driver was to begin operations. After the men in the water were properly stationed and comfortable the signal was given to the drivers by the man in charge of the trappers. They driver then made his appearance to the ducks, some distance away and the latter started swimming away towards the trappers. Directly they passed over the heads of these men they were instantly pulled below and their necks twisted under the water, where the trapper held them between his legs. What ducks were left approached the next zig-zag line of men to meet the same fate. This description, to inexperienced reader may appear far drawn, but as I said at the beginning of this article, I had the privilege of witnessing this method, by which two or more men could take part. There is still another way, which requires a large number of men to carry it out effectively. The blacks always have a good idea of the places where the ducks are to be found. A careful scout is sent out to locate the game then the hunters approach both sides of the waterhole simultaneously, being careful to avoid being seen or heard by the ducks and at a given yell by the leader every man rushes in as near to the top of the bank as possible, making the usual hideous screams, which terrify the ducks and make them fly straight up in a flock only to be cut down by the game boomerings, and a number fall in the dense weeds and deep water. Very often a number are only wounded and not killed outright, in which case the efforts of the expert water men are required to capture the birds. The blackfellow does not attempt to swim in these dense beds of weeds, but crawls over them like a water lizard, and from this the white men can easily take a lesson by remembering that the hand over hand crawl stroke is the most effective one to get clear of a danger of this kind.

FISH

As this tribe of aboriginals had access to the coast through Beaudesert and on to the southern half of Stradbroke Island they knew all about the use of nets. They made both the large and small nets from the leather wood tree bark which grew in most of the mountain scrubs of their country. They also made their own fishing line from the same material but in my time they always used the steel fishing hook. The nets are used in precisely the same way as below the range, viz., the drag net with which they cleaned up any holes, particularly small ones, by dragging it right through. Should the net be snagged they went into the water, and, by diving, cleared it. The small bag net was used principally by the gins and children, who frequently went into the holes and by stirring up the mud and making the water thick, easily scooped up the fish that came to the surface. They had another style, by spearing the fish, particularly the roney or swallow-tailed bream. In this sport they had a driver who brought the shoals along towards the men with spears amongst them, and I have often seen them get two fish on the one spear. Until I showed them how to use a fishing line attached to the end of a spear through a hole, like a harpoon, they always had to go into the water for the spears and fish. As they had, of course, never seen the harpoon used they considered it a wonderful invention and immediately made use of it. The large barbed spear was used for big cod fish in shallow water. The blacks were very fond of fresh water turtle, which they easily killed when basking in the sun on the logs or during the laying season, when these creatures came out on the banks of the streams to lay their eggs in the ground.

It is not generally known that the implements were the means of leading up to friendly intercourse between the tribes in the way of barter. The stone tomahawk was only made by the tribes who had the suitable stone, which was generally found along the main range, and these were of great value in districts where they could not get the material to make them. Again the boomerings were made from the Booyong (or Black Jack) tree, which was considered the finest timber to be had for that purpose. Both of these were easily obtained in the Blucher’s tribe’s territory. In exchange, the Blucher’s received principally spears made out of myall timber, which was particularly adapted for these weapons, as this kind of timber did not grow in the “Blucher” country.

SUPERSTITIONS

The “Blucher” tribe as far as I could ever find out, had no religion. They believed in magic and Devil-Devil, and further, were intensely superstitious. They believed that certain men who had a grudge against them had the power to kill them with what they called a Muddlo. It is necessary to explain to the reader what the Muddlo really is. It is a piece of crystallised quartz, and is generally found in the conglomerate and other formations of the precipices of the Main Range, being hard to get from those places. Sometimes this quartz can be seen 200 feet up, sparkling like glass in the sunshine. It was the cunning old rogues that were supposed to have the Muddlo, and the young people being in the camp with the old villians and hearing the latter relating stories about the wonderful power they had with the Muddlo, made them afraid to go over those places where the stone was supposed to be found, unless in company with a number of old men. The stories told the young by those old rogues puts me in mind of the stories of Wilson’s “Tales of the Border” or in the tales of the Arabian Nights.

The gins had mortal dread of the Muddlo, and the young men had the same fear. The idea the blackfellow had about the Muddlo was that it was formed in the rock by poisonous water. If a man got one, placed it secretly in a waterhole at night, and should a man or woman belonging to a neighbouring or their own tribe, having a personal grudge or thought to be an enemy, drink the water from that hole he or she would be instantly struck with a pain in the chest, and would remain sick for a few days, ultimately dying provided the medicine man did not come along. It would not affect anyone but the person it was intended to kill. When an aboriginal got sick for a few days with a pain in the chest, or anywhere else, he or she imagined they had come under the influence of the Muddlo. If asked what was wrong, they would say “Pigull, muddlo yacca warlow”, meaning that a blackfellow had been made sick by the Muddlo, and unless a medicine man sucked the Muddlo out they would die with fear. The medicine man, the rogue, would then come to the rescue and by a tremendous lot of sucking and ceremony would finally make a grimace and pretend he had extracted the Muddlo, when, as a matter of fact, he had a small Muddlo in his mouth all the time. During the time this operation was taking place there was no person present except the medicine man and his patient, and it was always the finale for the medicine man to let his patient see the small piece of quartz which had lost all its power only as far as the patient was concerned. The patient invariably got alright.

I shall now give an incident that came under my personal observation, of an unfortunate accident (because it was an accident pure and simple) in connection with a Muddlo and the tragic after-effect

In the year 1858, at the old water saw-mill at Old Killarney there was a Blackfellow called Jackie Jackie who was supposed by the young blacks to have a Muddlo, and they told this to a select few of working men at the mill. After work was finished, at evening, Jackie Jackie usually came round cadging tobacco. The men who had tobacco refused to give him any unless he would show them the Muddlo. He seemed greatly surprised and denied having one, but after a lot of coaxing, he consented to show the stone. He sat down on the ground and took a very small packet from his armpit, where he always carried it, attached to a string over his shoulder. There were 6 of us standing around him, and after glancing carefully around to see there were no blacks about, he opened the packet, unwinding a piece of rag. I expected to see something wonderful, so did the others, but we were rather disappointed when it turned out to be a piece of crystallised quartz. As we were busy examining it up came a young gin from behind the blackfellow, and glancing over the shoulders of the white men, inquisitive to see what we were all looking at, saw the Muddlo. She straightaway uttered a piercing scream and ran for the camp. Jackie Jackie sprang to his feet and raced to the scrub for all he was worth. That was the last seen of him by any white man excepting myself. The gin took ill and never left the camp until she was taken away a corpse three days afterwards. The same night that the gin saw the Muddlo two Councillors were told to watch Jackie Jackie camp, and about 2 am he came sneaking to the camp, hoping to obtain his war implements. Both Councillors immediately sprang out and gave him a start and ran for about a mile in the direction of where they knew there was a large hollow apple tree. They knew this tree was beyond the hearing of any person and on reaching the spot, closed in and drove their spears through the criminals chest, killing him on the spot. One of the Councillors took the precaution to have his vine with him which was instantly placed around Jackie Jackie’s neck, and he was drawn up and dropped inside the hollow tree. Some six weeks after this took place, I was catching opposums for skins to make a rug when climbing a large tree which was very hollow, and looking into the hole in front of my face. I saw Jackie Jackie’s bald head. As it was just twilight, my readers will not be surprised to know that I hurried away from such uncanny and disagreeable surroundings as quickly as possible.

I shall now tell how I found out about the native execution of Jackie Jackie and as the information was obtained from blackfellows of his own tribe who had passed the Bora ceremonies I knew it was to be relied upon as the truth. In passing, I would add that if any of my readers should have occasion to have any transactions with aboriginal men, where absolute truth was essential, I would recommend them first to find out if these men had been through the Bora, if not, place no reliance upon their facts.

Sometime in 1869 I was out mustering wild cattle on the head of Swan, Emu and Farm Creeks, also the Condamine River, having three black boys with me named Boni, Jab and Carlo, Carlo was a most amusing character, full of life, fun and good humour, but much older than the other two. I will refer to him later on, but in this instance, his work was to look after the “coaches” or quiet cattle used as decoys to trap wild cattle. On one occasion after we had finished mustering on the branches forming Emu Creek, we decided to drive our 60 “coaches” over the high mountain that divides Emu and Farm Creeks. On the following morning it was found that more than half of our stock horses had strayed away over night, so my brother, another white man, and two black boys went in search of them, intending to shift camp and follow on with the pack horses, etc. Jab and I taking the “coaches” over the high mountain. This proved a difficult job getting them through between the high precipices where there were no cattle tracks or pathways. With care and perseverance, we managed to get them onto the head of Farm Creek just as the sun was setting in the middle of July, to find that our mates had not arrived there as arranged, with our blankets and food, through having been delayed in finding the lost horses. They had the camp on top of the mountain some miles from us through darkness overtaking them. Jab and I therefore found ourselves in a bad position, not having tasted food since early morning and none with us, so there was nothing left but to hobble our horses, light a fire, gather sufficient firewood to see us through the night, and generally make the best of a hungry cold night, at an elevation of 4000 feet above sea level in the middle of winter. With a view of sitting the night out, I thought it would be a good idea to get as much of the customs and laws of the “Blucher” tribe from Jab as possible. The first question I asked him was did he know Jackie Jackie. He looked very hard at me for some seconds before making any reply, as if considering what to say. He seemed very surprised, and finally said “You been know ’em that fellow?”, I replied that I did. He then remarked “that fellow been ‘cabon’ rogue” (cabon meaning big). Evidently it dawned upon him that we were then between two precipices which he had previously shown me as where the Muddlos were to be found and becoming nervous and excited related the History of the gin and the Muddlo, which the reader already knows. It appears that after the gin reached the camp and told what had happened there was a great commotion in the whole camp, the men in small groups whispered together and the gins as silent as death, as if afraid to speak. Apparently, the Muddlo creates fearful terror to the gin who has seen it, which aggravates their death unless a medicine man is on the spot. In this instance Jackie Jackie absconded and his witchcraft was exposed. When I asked Boni and Carlo they corroborated Jab’s statement.

In a sense the Muddlo was a strong point in the white man getting control over the blacks, because they considered the Muddlo was also connected with lightning. They had seen some of their own people killed by lightning, and when the white man began to use firearms, the blacks seeing the flash and not the bullet, connected this power with lightning to our advantage.

REMEDIES

Cunjevoy Sting or Poison: The remedy the blacks had for this was to fill the mouth with wet or damp soil free from vegetable matter, which will give instant relief. I have never known it to fail. I am giving this cure here as it may benefit some sufferer who has been foolish enough to taste it. It has always struck me that the juice of this plant would be antidote for snake bite, as snakes will invariably be found where it grows, and I have asked blackfellows if they have ever tried it for the purpose, their reply being that they knew nothing of its properties in that direction, only for food.

I have often thought that immigrants coming into the country should be warned against tasting anything growing in the bush unless first see the birds eating it, as instinct has taught the latter not to eat anything poisonous.

Snakebite:- For this, there was no antidote except that a ligature was immediately applied if the wound was where this could be done. The material was the loin girdle worn by every gin, which was made out of marsupial hair. After the ligature had been twisted up the wound was scarified and made to bleed, every native present taking their turn at sucking it, provided, of course, there was nothing wrong with the gums or mouth, afterwards rinsing their mouths out with water. This process went on until all danger was passed.

Choking Child:- As this was not an uncommon event amongst the piccaninnies, the blacks had a very simple effective way of treating a child who had tried to swallow something too large, viz; they grasped the child by the legs, and sprang into the air, giving the child body as sudden a jerk as possible, which soon had the effect of making the child vomit up the obstruction.

Wounds and sores:- These were usually treated by the application of water and soil, or in the other words mud. The white people generally had a wrong conception of the use of poultices made from earth, in that they thought any kind of bad soil was used in making the Bora tattoo marks fester and stand out afterwards when covered by the natural skin. For any cut they used pure soil and water with which they made mud poultices at the edge of the water. They were very careful about the temperature of the water, and I judged it to be about 75 degrees as the favourite heat. They could not use very cold water. I have seen all kinds of ghastly cuts healed in this way, one in particular being a warrior cut from the buttock to the back of the neck along the edge of the spine as a result of a tribal fight with the Mcintyre River tribes. That part of the wound near the shoulder blade exposed the lung, over which a piece of material was placed by my mother, so as to prevent any of the mud poultice getting inside. This man made a complete recovery. Whenever possible they were always particular to have the wound washed by clean water after using the mud poultices. As soon as the inflammation went down the wounds were anointed with iguana oil.

SOCIAL EVILS

The first sign of this which I saw amongst the “Blucher” tribe was in the early sixties when I came upon two of the young blackfellows whom I knew personally camped by themselves in the vicinity of the “Coal Hole” on Farm Creek. Considering this strange I wanted to know the reason and was reluctantly told by one that “Yerilee chung, cabon muddlo yaacca warlow”, meaning the white fellow had made them sick with his disease. That was my first observation of the scourge, which prior to the advent of the white man, was unknown to the aboriginals. Those words coupled with the most contemptible oath of the Aboriginal, “Chung”, still ring in my ears as the undeniable truth and to be told it by the savage in his own expressive way has often made me think very little of my race. These young fellows told me that the only remedy they could think of was to use the Coal Hole fresh water pool as a bathing place because the tribe had no previous knowledge of the disease or how to treat it; consequently, they used to lie in this water for hours at a stretch and eventually cured themselves after a considerable stay at that place with no other treatment.

The “Coal Hole” was so named because a large seam of coal appeared to form the bottom and walls of the spot, and an everlasting stream of water trickled from the coal seam into the pool. That the water had medicinal properties of a beneficial nature was evident, and further, that the aboriginals knew this, was impressed upon my mind. No doubt the medical profession know something about the reason why the water was as effective. As a diversion I shall remark that prior to this the “Coal Hole” was pointed out to a Scotsman named Bill Murat, who was an educated man, but like many others at that time was a working man on Canning Downs. Murat recognised the importance of the coal seam and tried to persuade the owners of Canning Downs to work or open it up, also other, but met with no success and nothing was done until many years after his death.

CARLO THE CORROBOREE COMPOSER

Carlo was a great favourite amongst the blacks, and was their principal man in composing songs for the corroborees. Another thing I found him most useful for was that he knew the names of all the timbers and places. I also employed him on our mustering trips, particularly to look after the “coaches”, and recollect my first experience of his happy nature. We were sneaking to get between the wild cattle and scrubs, every moment to be done as quiet as mice, when Carlo suddenly broke out with his wild aboriginal songs and spoilt our chance of getting the wild mob on that occasion. After this Carlo was put in charge of the coaches and played his part well. In appearance this blackfellow was one of the finest specimens of humanity to be found, just the ideal that the teachers of physical culture love to work up to. He was 6ft2ins high with massive shoulders and large arms, splendid body carried by muscular legs tapering down to feet that would show off No.8. boots. This man’s head was large and looked altogether different from that of the ordinary aboriginal, both in shape and size, being more the shape of a good white man’s head. The usual black piercing eyes sparkling with fun and good humour made him a most intelligent and agreeable bush companion, and lit up a splendid athlete.

When the Bunya season was on the “Blucher” tribe were regular visitors to the Bunya Mountains near Dalby, where other strange tribes also congregated consequently new corroborees were the order of the season so far as Carlo was concerned. I was greatly surprised at seeing his first notes of these, which was recorded on the inner bark of some tree, in the shape of figures of me and animals painted with a kind of pigment mixed with iguana oil. These sheets were carefully rolled up like brown paper and protected from the wet. From these notes, he composed his corroborees and the tribe rehearsed them until they were proficient, and then gave them to the visiting tribes after the Bora ceremonies.

GENERAL